Minibytes by Al Allen

Training typically includes classroom sessions, workshops, drills, field exercises, etc. Regardless of the format and location, there are some basic guidelines that help make such training effective. My own observations on this topic draw from about a thousand training sessions over the past 5 decades. Conducted in well over 75 countries, involving tropic, temperate and arctic conditions, I’ve noticed a trend in what seems to work well, as well as what doesn’t. I won’t comment on the obvious, such as: qualified instructors with good speaking skills, interesting subject matter, comfortable classroom conditions, good equipment/vessels/aircraft for field support, etc. Instead, I’d like to point out a fundamental shortcoming that I’ve witnessed several times over the years.

Selection of Trainees: A well-trained Oil Spill Response (OSR) Team, experienced with response strategies and tactics; fully aware of each member’s Incident Command System (ICS) role and the regulations and documentation for that position, is essential. Classroom sessions, followed-up with field exercises and drills, are commonly used to keep the OSR Team functional and well-prepared. Unfortunately, such training often leaves out individuals that will be counted upon to “execute” critical activities during an actual spill response. This is especially true at an operational level where the pilots, captains, crews and support personnel for aircraft and vessels may get to participate in some limited field exercises or demonstrations; however, they are rarely given the classroom instruction needed to fully understand and carry out their roles during an actual spill event.

A brief example of the above-involved training that I carried out abroad for a major oil company several times a year over a 10-year period. The company’s OSR Team members became quite competent and confident in areas including ICS functions and offshore response including skimming, controlled burning and the application of dispersants. However, I found that the Captains of response vessels and their crews (especially “salty”, stubborn, contractors with other more important day-jobs) often had their own strong opinions on how to operate at sea. Some, it seemed, needed special time-consuming advice that was rarely accepted easily during the execution of a training or actual spill event! Such discussions might focus on why an oil containment boom should be towed at a knot or less to minimize oil loss, when the Captain was comfortable with the goal of an average tow speed of 1 knot, towing at 2 to 3 knots and then coasting for a while.

Worse yet, was the time when a company for whom I had been training abroad was becoming increasingly disappointed in the apparent ineffectiveness of their dispersant application program. All personnel on the company’s OSR Team were quite supportive and experienced with the proper use of dispersants, and the dispersant stockpile and equipment had been well maintained. A lack of training with a few new contracted vessel Captains, however, had allowed a misconception to spread among that contractor’s personnel at sea. It took several visits for me to finally get a crew member on one vessel to open up about their concern: “Since the oil treated with dispersant quickly disappears off the surface during actual spill events, it must be paving the ocean floor and destroying all marine life at the seabed”! To my shock, he also mentioned how they would deal with this problem by pouring the dispersant overboard in clear water on the way to a spill, and then simply “look good” by spraying sea water (without dispersant) on any spilled oil! I quickly visited all potential spray vessels in the area, and patiently explained the basics of dispersant use and its impacts upon oil and the environment. I made it clear that dispersants do not sink oil and “pave” the ocean floor. While protecting the confidential disclosure of the contractor, and likely saving the jobs of a few “new believers in dispersants”, I also got my client to expand its training, including those who often carry out key sub-contracted functions.

While there are many other training-related lessons to share in future blogs, I did give a few hints in my last blog (#7) about a personal lesson I hope you never experience. A loooong time ago I had been participating in a 4-day training class for CISPRI, an oil industry OSR cooperative in Kenai, Alaska, managed at the time by Captain Barry Eldridge (now deceased). By the end of the 3rd day, I had developed such a sore throat that I could barely speak. Barry, feeling sympathy but also needing me to complete the course, purchased a speaker and remotely-operated microphone that could be placed in my shirt pocket with the microphone very close to my neck. The class could now hear my faint, scratchy voice for the 4th day of instruction. By mid-afternoon I was struggling enough that Barry offered to give me a break, and then lecture from my notes on a topic with which he was already comfortable. Nice Guy!

He was off to a good start as I rested at the back of the classroom. Thinking that I would slip away for a few minutes to the restroom, I did so, and soon realized that Barry was apparently a much better speaker than I had imagined. Since he was on a roll with some good stories (based on the laughter in the other room), I decided to extend my restroom visit, and take care of what seemed like a pending late-afternoon “dump”. I know you can already imagine the lesson learned in this story, but I will continue anyway.

As I sat, coughing quietly and gagging from both throat pain and my own on-earthly emissions, I could not help but be a little annoyed at just how really good Barry must be filling in for me! As I completed a series of high-pressured sprits and dribbles, a few final plops, and the seemingly unending paper-work, I flushed, washed my hands, and headed back to the classroom to resume my portion of the instruction. As I stepped into the room, I was surprised to find the entire class standing, looking back at me and applauding. Still oblivious to why they had appreciated and missed me so, I nodded a “Thank you”, and as the applause subsided, Barry choked a tear-filled, giggle-ridden warning to me: “Alan, the next time you use a restroom with a remote microphone…,” painful pause…, “do turn it off !” It was truly hard to lecture the rest of the afternoon, thinking about the acoustically entertaining event I had just created.

It is satisfying when students remember you for an outstanding class they attended years ago. But, when one of them recognizes me passing at the mall or at the airport, and says: “Hey, I still remember that class when you…” Man, that’s a lesson I wish I could forget!

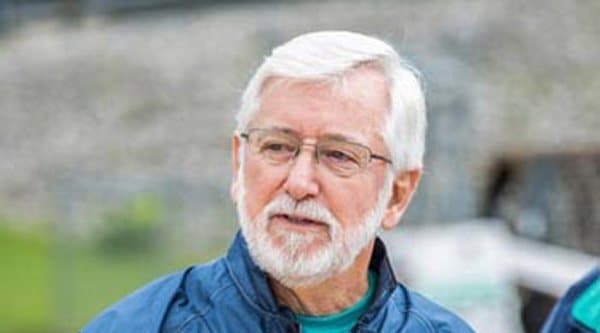

Alan A. Allen has over five decades of experience as a technical advisor and field supervisor involving hundreds of oil spills around the world. Al is recognized as a leading consultant and trainer involving oil spill surveillance and spotting techniques, the application of chemical dispersants, and the containment, recovery and/or combustion of spilled oil under arctic and sub-arctic conditions.

Copyright© 2018, Al Allen. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author is prohibited.